My previous article, Observations from the Global Legal Hackathon 2018: The Communal Dimension of Intellectual Property, considered the challenges in finding the right intellectual property norms for the unique context of a hackathon, where newly acquainted groups of project managers, lawyers, UX (user experience) designers and business students work cohesively and intensively. This article is about the tensions that collaborative disruption can create.

Most lawyers who attended the Global Legal Hackathon have heard the sensationalist claim that lawyers will be replaced by machines. They also know that the arguments behind this claim are much less radical than they sound. If automation involves merely outsourcing a certain amount of legal work to technology professionals, then this fails to challenge the existing pyramid structure of legal work. For example, technology-assisted review removes the type of work traditionally performed by paralegals and more junior lawyers. This has ramifications for the hiring and training of junior staff, but doesn’t affect the core work carried out by more senior staff.

Disruption is hard work

Beyond outsourcing, the dynamics of the legal technology sector become much more complex. The involvement of lawyers in the development of new technologies and ensuring that such technologies comply with statutory requirements is essential, particularly because it ensures that solutions are designed to meet the needs of lawyers and their clients. Just as software engineers must continually intervene by updating and redesigning apps, lawyers must step in whenever statutory and regulatory requirements change, to generate new legal content, and to address compliance and potential liability issues.

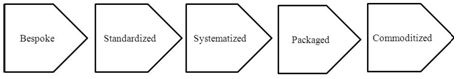

One team in the Sydney Round of the Global Legal Hackathon, Say When, pitched an app that would keep small businesses updated about their periodic licensing and permit requirements. This goes some way towards automation, but it’s better understood as part of the process which Richard Susskind described in his book Tomorrow’s Lawyers, in which services are transformed into products (while nonetheless retaining an important service component).

This kind of technology isn’t inconsistent with the work of big law firms such as Allens, King & Wood Mallesons, DLA Piper and Gilbert + Tobin, which are engaging technology to streamline their workflow and service provision. Indeed, NewLaw firms such as LegalVision have been founded on this very premise. Seen in this light, the question of lawyers being replaced is rather a question of whether the impetus towards different kinds of commoditisation will come from inside or outside the legal profession.

In an economy dependent on high levels of specialised expertise, “hacking” culture champions the outsider, the self-taught renegade who exploits systemic rules rather than following them and brings to light the unknowns that are unknown to those inside an industry. But this outlook neglects the unknown knowns – the knowledge that professionals accumulate about their assistants, bosses, partners and clients, as well as the values, tools and discourses underlying their working lives, which are rarely made explicit until they’re challenged. The Sydney Round of the Global Legal Hackathon gave several insights into how individuals leverage their insider or outsider perspective, or move beyond it.

Shifting perspectives

The winning team, CourtCover, was predominantly composed of individuals with legal backgrounds. Its idea was a simple tool designed to ease communication between lawyers and potential legal agents. Other teams of a similar composition likewise were less concerned with disruption and more interested in facilitating communication and enforcement in novel ways. HealthMatch designed a pragmatic tool to facilitate links between ill patients and clinical researchers while exposing only the minimum necessary amount of sensitive patient information, and Silky sought to link clients and barristers directly through smart contracts. As insiders of the legal profession, lawyers are faced with significant complexity and information overload on a daily basis, so it’s natural that in this context they would focus on technological solutions that simplify work and communications.

By contrast, the Morphic Solutions team, predominantly composed of consulting analysts, technologists and web designers from the company Hypereal, conceptualised what was perhaps the most ambitious app of the hackathon – a form of contract automation that shifts the task of agreeing on certain terms away from clients and onto a set of algorithms based on the reputations and priorities of respective clients. This particular project relied on the assumption that many parties’ reciprocal commercial activities are built not on the finer details that make up a contract, but rather on existing trust relationships and values.

If we consider that, in the context of such a technological solution, lawyers would still play a central role in drafting a range of possible clauses that reflect the standard practice of various industries, and incorporating feedback into the wording of clauses, it’s ironic that this app was designed by a team largely composed of non-lawyers. Likewise, a team from PricewaterhouseCoopers developed Incident.ly, a program which would give lawyers a significant degree of immediate control in crisis situations such as data breaches. Rather than challenging the importance of lawyers, these teams envisioned new roles for them.

TelcoPal, a team of six in which only two members had legal industry experience, relied on significant market research from outside the legal industry to shed light on complaints to telecommunications companies. Perhaps this is an area that private practice lawyers only rarely deal with, as it concerns relatively small claims for which most clients wouldn’t pursue legal action. While not challenging the scope of legal work per se, such a project does expand the scope of dispute resolution in a consumer context.

Throughout the hackathon, it was clear that lawyers were learning from tech specialists and vice-versa. But, reflecting on the decisions of these teams, perhaps the most productive leaps came when the lawyers attempted to look at their industry through the eyes of tech specialists, and when tech specialists did the converse. By putting aside the obstacles they encounter in their regular occupations, and by seeing that the legal or technological strategies they’re used to working within are no more than means to an end, participants were able to come up with highly effective solutions.

By contrast, whenever teams set about assigning tasks predominantly based on individuals’ respective skill sets, with developers working back-end, and lawyers and consultants working front-end, teams would speak different languages, become more tunnel-visioned and neglect the creativity required to solve the problems they had set themselves.

Final thoughts

Clayton Christensen’s theory in The Innovator’s Dilemma observes that innovations that begin on the margins of an industry will over time disrupt the core functioning of businesses, radically transforming the workplace and relationships with clients. Whatever conclusions we may draw from the events that took place over the course of a busy and inspiring weekend, it’s clear that the power of individuals to innovate isn’t defined by their position at the core or margin of an industry, but that they may readily move between them in order to find new forms of knowledge.

The Sydney Round of the Global Legal Hackathon, which was co-sponsored by Thomson Reuters and Herbert Smith Freehills, took place between the 23rd and 25th of February at the University of New South Wales. The event involved approximately 60 hackathon participants and was organised by a raft of volunteers from The Legal Forecast and 23Legal and a range of mentors, including technology, sales, legal and strategy mentors from Practical Law Australia and other teams within Thomson Reuters.