Australia’s long-awaited Tranche 2 anti-money laundering (AML) laws have become the victim of a departmental reshuffle, a process known in political circles as being “mogged”, according to a senior bureaucrat.

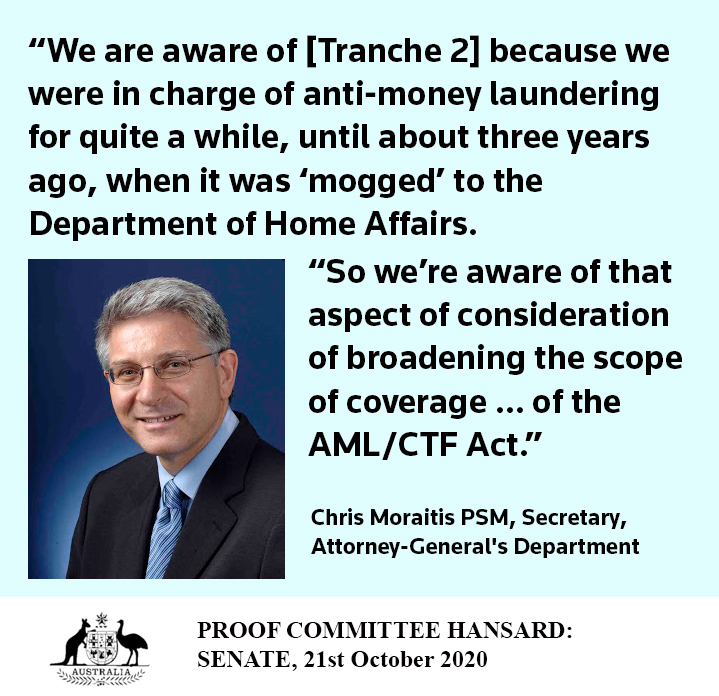

Chris Moraitis, secretary of the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD), told a Senate committee hearing in Canberra that the laws to bring gatekeeper professions within the AML regime had been delayed following the creation of the Home Affairs portfolio in December 2017. The changes to “machinery of government” (MoG) meant that the AGD lost control of the policy reforms.

“We were in charge of anti-money laundering for quite a while, until about three years ago, when it was ‘mogged’ to the Department of Home Affairs. So, we are aware of that aspect of consideration of broadening the scope of coverage,” Moraitis said.

For the past 14 years the laws to include designated non-financial businesses and professions (DNFBPs) under the AML/CTF Act have languished, the Senate was told.

The hearing was relayed comments from John Chevis, a financial crime consultant and former Federal Police officer, who said the failure to pass Tranche 2 of the AML/CTF Act had created a glaring vulnerability in the Australian economy.

“The first thing you do [if you want to launder money] is find yourself a referral agent. That person will be a lawyer or an accountant. He will help you set up a trust and company in an offshore jurisdiction that has access to a bank account, preferably in another offshore jurisdiction,” Chevis said.

Tranche warfare

Gatekeeper professions were just one of the many laundering vulnerabilities in Australia, said Nicole Rose, chief executive of the Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre (AUSTRAC).

“Sadly, there are a plethora of ways that you can launder money. Certainly, using professional facilitators is one of those ways,” she told the Senate.

The financial intelligence unit is precluded from commenting on Tranche 2 policy, which is a matter for government, under long-standing public sector policy guidelines. The AUSTRAC chief acknowledged, however, there was a criminal intelligence gap as a result of the failure to move on Tranche 2.

“They’re [DFNBPs] not required to report to AUSTRAC under the legislation. I would expect that any law-abiding professional would report criminal activity, but they’re not required under the legislation,” she said.

Movement of money

Chevis said: “Everyone in the world who is involved in AML/CTF knows that lawyers, real estate agents and accountants are well used by people who have illicit wealth to transfer.”

Rose told Senate estimates AUSTRAC was aware of cases where “corrupt” lawyers, real estate agents and accountants had helped criminals to launder their illicit profits.

“I wouldn’t want to make the statement to make it sound that there is a large percentage of lawyers, accountants and real estate agents out there doing the wrong thing. Certainly, though, it is recognised that organised crime, in particular, use professional facilitators — that is, corrupt lawyers, real estate agents and accountants — to assist them in the movement of money, among other things,” Rose said.

Statutory review

Recommendation 4.6 of the statutory review into the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Act 2006 said the government should develop options to include DNFBPs as designated service providers.

The commitments were under consideration by the government, Rose said. There had been a discussion within Home Affairs earlier this year on the Tranche 2 reforms but she could not specify when the dialogue took place.

“Certainly, we work very closely with Home Affairs, as the policy department, on all of those issues relating to the legislation. We’re currently looking at updating a number of areas, so we regularly consult with them,” Rose said.

AUSTRAC estimated in 2016 that A$1 billion was laundered through real estate in Australia from China alone. The agency relies on estimates, however, and lacks any more up-to-date numbers, Rose said.

“We tend to refer to the 2 to 5% of GDP figure for money laundering in general. So, we don’t have a specific real estate figure. The ACIC may, but we don’t have that information,” she said.

A recent report from Initialism, a consultancy, said that only six Financial Action Task Force (FATF) member countries had failed to move on all three of the recommendations relating to DNFBPs. These were Australia, China, Madagascar, Mauritius, Mongolia and the United States.

“While Australia, as a member of the FATF has been subject to international standards since 2003, the debate about the AML/CTF regulation of DNFBPs in Australia appears to be bogged-down with inaction, hyperbole, and scare-mongering,” the report said.

“Despite DNFBPs being identified as a gap in Australia’s AML/CTF compliance regime since at least 2005, as well as promises to address the issue made by the Australian government, little or no progress has been made by Australia to bring DNFBPs into its AML/CTF regime.”

This report was written by Nathan Lynch, APAC Manager, Regulatory Intelligence, Thomson Reuters.

Webinar: Beyond the FinCEN files: Building a better framework for financial intelligence

Join Michael Messier, Robert Mazur, President, KYC Solutions Inc and Nathan Lynch for their discussion on the future agenda for AML/CTF compliance.