By Stan Hales, Partner, Janelle Sadri, Account Director, and Gemma Cowan, Manager, Transfer Pricing, Deloitte

Introduction and background

Some industries have enjoyed a boom in 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, whilst other industries have been thrown into turmoil, as government mandated physical distancing, widespread industry shutdowns and a broader global recession impact both profitability and business viability.

Over the past 6 months, many businesses have had to close (either temporarily or permanently) because their operating models are incompatible with the strict self-isolation rules.

Those businesses that have continued operating have likely had to re-engineer their whole service offerings and workplace environments, against the backdrop of weakening consumer demand and confidence, global supply chain disruptions, and even the health impacts of the virus on their workforce. Whilst the long-term economic impact of COVID-19 on the global economy is unlikely to be known for some time, real gross domestic product (GDP) in OECD areas showed an unprecedented fall of 9.8% in the second quarter of 2020 [GDP Growth – Second quarter of 2020, OECD].

As COVID-19 containment measures start to relax, the real work starts; to save the thousands of businesses and jobs affected by the economic downturn.

In a transfer pricing context, a decline in GDP has meant that some multinational enterprises (MNEs) are experiencing losses across the value chain, and several new and unexpected risks managed by related parties either contractually or operationally, have materialised in unforeseeable and unprecedented ways. Against this backdrop, now is the time for MNEs to consider changes to transfer pricing policies. These transfer pricing policy changes should involve addressing the following questions:

- Have related party entities in the MNE’s value chain experienced changes to their functions performed, assets owned / utilised, or risks borne?

- Would these changes warrant a change in the transfer pricing method(s) applied or profit level indicators used, for example, in a Transactional Net Margin Method (TNMM) analysis?

- Could the profit (or loss) split method be considered more appropriate (at least for 2020) to spread the impact of a recession amongst the entities within the multinational group?

- From a practical perspective, have MNEs reviewed their inter-company agreements for risk sharing clauses or entered into any new intra-group transactions?

- Are MNEs collecting the right quantitative and qualitative evidence to be able to demonstrate to tax authorities, perhaps years after the event, the real impact of a recession on their business?

In light of the above questions, and as governments come under increased and sustained fiscal pressure, tax administrations are likely to expand their transfer pricing review and audit activity. Accordingly, this article provides practical guidance that MNEs should consider to help ensure their transfer pricing policies and tax return filing positions remain defensible in the light of the commercial changes necessitated by COVID-19.

Reviewing the functional, asset and risk (FAR) profile of the entities to a related party dealing

As a starting point, before reconsidering the transfer pricing method selection, MNEs must consider whether the functional, asset and risk profiles of their group entities have changed as a result of COVID-19. For instance, is an entity is performing less or new additional functions, developing new IP, utilising new or different assets, or bearing / controlling less or additional risks due to COVID-19?

For example, earlier in the year, a reallocation of business functions may have occurred a result of the majority of the work force having to work from home. Businesses may also have set up crisis management centres and incurred increased expenditure on virtual communication tools such as video conferencing technology. Asset values may have declined due to underutilisation or reduced market demand for the asset. The entities which incur these costs should be compensated by the beneficiaries of these services.

Functions aside, revenue authorities will be particularly interested in understanding what new and incremental risks have materialised during the pandemic, given the OECD focus on risk allocation and value creation as part of the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project. It will be especially important for businesses to now consider who is actually, in practice and in real time, bearing the keys risks that have impacted sales / business operations during the pandemic.

Key questions MNEs should be considering are:

- Which entities have historically been bearing the key risks in respect of intercompany transactions?

- Have these entities maintained this risk profile throughout COVID-19?

- Are these entities wearing the financial downside associated with these risks materialising?

- Have any new key risks materialised as a result of COVID-19 and who is responsible for managing these new risks?

As per paragraph 1.56 of the OECD Guidelines [2017 OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations], “a functional analysis is incomplete unless the material risks assumed by each party have been identified and considered; since the actual assumption of risks would influence the prices and other conditions of transactions between the associated enterprises.” Furthermore, paragraph 1.56 goes on to state “the level and assumption of risk, therefore, are economically relevant characteristics that can be significant in determining the outcome of a transfer pricing analysis”.

The implication is that higher risk translates into higher rewards. The converse would also apply, such that the risk bearer also accepts the losses from reduced demand and a decrease in sales. Therefore, if it becomes evident that the allocation of risks amongst entities to a transaction have changed, or new risks have arisen that may impact entities risk profiles, through a decline in sales or an increase in expenses, this may warrant revisiting the arm’s length return that each entity receives.

Factors relevant to transfer pricing method selection

Transfer pricing methods are used to test the arm’s length nature of prices to ensure that international related party transactions conform to the arm’s length standard. The aim is to select the most appropriate method (capable of reliable application) for a particular case. In choosing the most appropriate and reliable method to test the arm’s length nature of an intercompany transaction, consideration is given to the following:

- The respective strengths and weaknesses of each method;

- The nature of the controlled transaction;

- The public availability of reliable information and pricing data needed to apply the selected method; and

- The degree of comparability between the controlled and uncontrolled transaction.

The OECD Guidelines state that no one method is suitable in every possible situation, nor is it necessary to prove that a particular method is not suitable under the circumstances.

The TNMM tends to be commonly used to support the returns achieved by service providers, and sales and distribution entities. The TNMM compares the net profit realised in a controlled transaction to the net profit realised by broadly similar independent parties in similar transactions in a similar industry. The TNMM makes use of a “net profit indicator” as a means for this comparison. This is a ratio of net profit relative to a base such as “costs”, “sales” or “assets”. As multiple net profit indicators can be used, and as the comparability standard for the TNMM is less stringent than, for example, the Comparable Uncontrolled Price (CUP) method, the TNMM is widely applicable and is the most commonly used transfer pricing method.

In contrast, the profit (or loss) split method tends to be less widely applied and is more of a ‘last resort’ given it involves a complex 2-sided analysis, usually without comparable market transactions. The profit split method identifies the combined profits for the associated enterprises from a controlled transaction and splits those profits between the related parties on an economically valid basis. Importantly, the OECD recognises that profits might be losses in certain circumstances, over short periods of time, such as a global recession. The resulting split should effectively approximate the division of profits or losses that would have been anticipated and reflected in an arm’s length agreement made between independent parties. An example would be a joint venture between 2 partners in a business.

Is another transfer pricing method more appropriate if the parties have changed FAR profiles in the current economic circumstances?

Under more normal economic circumstances and market conditions, transfer pricing policies seek to remunerate both/all parties in such a way that mimics arm’s length conditions between independent parties. However, during a recession, those same transfer pricing policies, which may have been in place for several years and are supported by extensive analysis and benchmarking, may now need to be revisited, albeit keeping the arm’s length principle as the cornerstone objective. Honouring these policies may be putting additional pressure on the principal or other entities in the value chain. The profit margin may indeed be a temporary loss margin, benchmarked with companies reporting losses.

Where the functional, asset or risk profile of the parties to an intercompany transaction has changed, businesses may seek to change the existing TNMM transfer pricing policy / method to improve cash flow through the pandemic and post-pandemic period. For example, with declining demand in a recession, businesses may seek to apply an alternative transfer pricing method such that both parties to an intercompany transaction bear some of the group’s losses. From a commercial perspective, it may no longer make sense that one party is insulated from the majority of profits or losses. Without formal indemnities and guarantees, no one party is exempt from the risks associated with an intercompany transaction, as the related parties in each country bear normal commercial, operational and legal risks.

The OECD Guidelines (2017 OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations), while not being prescriptive, clarify and significantly expand the guidance on when a profit split method may be the most appropriate method. One or more of the following indicators would suggest that the profit split method may be the most appropriate method to apply:

- Each party makes unique and valuable contributions, such as the joint creation of intellectual property or other assets;

- The business operations are highly integrated such that the contributions of the parties cannot be reliably evaluated in isolation from each other;

- The parties share the assumption of economically significant risks, or separately assume closely related risks.

The last factor mentioned above might be of relevance in the current climate, to the extent that additional / new economically significant risks are now materialising and affecting MNEs across the value chain as a result of COVID-19. For example, where there is clear evidence that the parties to a transaction genuinely now share risk, the profit (or loss) split method be considered more appropriate (at least for 2020) than the TNMM to spread the impact of a global recession amongst entities within a multinational group. In all cases, it must be clear that the profit split method is the most appropriate method to apply to price and/or test the intercompany transaction, as the OECD acknowledges that the profit split method should not become the default transfer pricing method.

Action 10 guidance states that the profit split method is the most appropriate method when, according to the accurate delineation of the transaction, the various economically significant risks in relation to the transaction are separately assumed by the parties, but those risks are so closely inter-related or correlated that the playing out of the risks of each party cannot reliably be isolated [OECD (2015), Aligning Transfer Pricing Outcomes with Value Creation, Actions 8-10 – 2015 Final Reports, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264241244-en].

The ramifications from COVID-19 apply globally, and losses sustained by businesses are not isolated to individual countries. Using the travel sector as an example, a fall in demand for a service in the global travel sector is due to the ban on travel, and is directly correlated to the COVID-19 response in different countries for each entity operating at various levels in the global travel industry. This impact occurs due to macro-economic factors, irrespective of transfer pricing considerations, such as the specific contractual delineation of functions and risks. Depending on further analysis of individual cases, this type of situation could potentially warrant an alternative transfer pricing method to be considered so that losses are shared between all the affected parties within an MNE.

As set out above, when selecting a new transfer pricing method, consideration should be given to the respective strengths and weaknesses of each method, the nature of the controlled transaction, the availability of reliable information needed to apply the selected method, and the degree of comparability between the controlled and uncontrolled transaction. Put another way, while COVID-19 may point towards a new and different sharing of risks and losses in the recessionary economy, a profit split may not be appropriate in a post-pandemic world. A transitional approach for exceptional circumstances may be appropriate as a short-term solution to address losses, which may revert to profits on a longer-term basis.

Practical considerations – reviewing inter-company agreements, and gathering the right evidence to demonstrate the impacts of COVID-19

Just as supply and other service agreements with independent parties may be reviewed during the pandemic, intercompany agreements should be revisited and MNEs should consider whether there is scope to:

- Invoke termination clauses, penalty notices, or force majeure clauses;

- Negotiate covenant holidays, payment deferrals or restructure credit terms, such as loan forbearance;

- Obtain parental guarantees in order to secure third party funding in the current economic circumstances;

- Amend the terms of related party agreements to mirror revised contracts with independent entities and customers (where applicable); and

- Enter into new related party agreements depending on any changes in counterparties based on changes to the global value chain.

From a dispute prevention perspective, tax authorities are cognisant of the impact COVID-19 is having on MNEs globally, but challenges may inevitably arise for those multinational groups financially impacted. For example, the ATO released guidance on how taxpayers should account for COVID-19 economic impacts on transfer pricing arrangements and concerns the ATO has on changing related party agreements in the COVID-19 environment. It is clear from the guidance issued that the impact of COVID-19 on transfer pricing positions is likely to be an area of focus for the ATO (and other tax authorities globally) over the next 18 months, if not longer.

Evidence is needed to explain and defend transfer pricing positions

Analysing and documenting the adverse impacts of COVID-19 for transfer pricing purposes is key. MNEs negatively impacted by COVID-19 should gather comprehensive evidence over the course of 2020 and into 2021 to help explain and defend their transfer pricing positions in the event of a revenue authority review. Such evidence may include:

- Analysis of how the company would be placed ‘but for COVID-19’, in line with the recent ATO guidance.

- The justification for (potential) reductions in revenues, profitability decreases or losses, including any significantly impacted profit and loss items.

- Commentary on how the taxpayer is controlling the impact of COVID-19 on performance and who within the MNE is controlling the major risks faced by the business.

- An overview of any transfer pricing policy changes and the rationale for terminating or entering into any new inter-company agreements.

- Board minutes, emails, presentations, TP documentation, news reports, competitor results or industry-specific information highlighting the impact of COVID-19 on financial results to support transfer pricing positions taken in 2020 with granular detail in case of tax authority enquiries.

- Contemporaneous transfer pricing documentation that tells a well-developed and coherent ‘story’ and demonstrates alignment between substance and form.

Check if transfer pricing policies are being effectively achieved

Finally, to ensure transfer pricing policies are being effectively achieved, MNEs should:

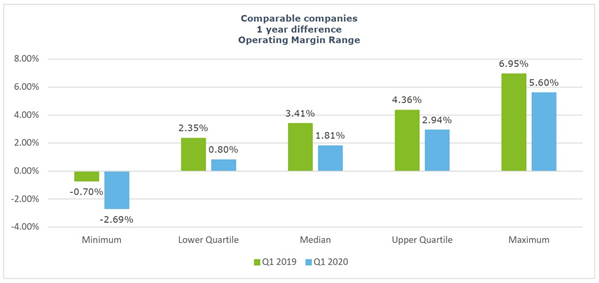

- Consider whether target and actual outcomes will still broadly align, if existing transfer pricing policies continue to be applied. Businesses may want to consider comparing target and actual monthly performance for the forthcoming months to the same months in the previous year, to help quantity the impact that COVID-19 is having on the financial performance of the business – Consider lower benchmarked returns – as benchmarking studies lag the current year and are based on comparable companies’ data from previous years, it is likely that certain comparable independent companies selected as part of transfer pricing studies, may report declining margins, or may incur losses in 2020 during the recession. Businesses may want to consider the use of loss-making comparable company financial ratios in a TNMM benchmarking analysis, or target the lower end of the arm’s length range, to support reduced returns during the COVID-19 based global recession. The graph below provides an example of declining operating margins in the US electronics distribution sector from Quarter 1 of 2019 to Quarter 1 of 2020, i.e. the start of pandemic [Financial data to compare the operating margin ranges was extracted from publicly available US SEC 10-Q filings for 14 distribution companies of electronic products]. While one quarter does not make a year and distributors of some products have not been adversely affected by COVID-19, we expect operating margins in different industries will decrease over the course of the recession in 2020.

- Assess the ability of systems and processes to reflect the costs of complying with the appropriate local application of policies, to ensure that cost charge-outs are correct for each beneficiary of the expenditure.

- Understand what cash requirements are needed to continue operating and consider alternative ways to support operating cash flow, for example through the deferral of royalty and interest payments if the facts and circumstances warrant change; perhaps with commercial evidence that the same changes occurred with third party customers and suppliers. Many lenders offered borrowers temporary loan payment forbearance, as an example.

- MNEs are encouraged to monitor whether local tax authorities have issued temporary concessions or guidelines to support businesses in applying alternative transfer pricing methodologies during the pandemic. For certainty, MNEs may wish to proactively engage with revenue authorities in relation to any Advance Pricing Agreements in place for which critical assumptions and conditions are at risk of being breached as a result of the impact of COVID-19.

Conclusion

As some MNEs are recalibrating their supply chains to manage the disruptions of a global recession, this may be the impetus for a change in pricing models or pricing policies, or a review of inter-company agreements, particularly where the sharing of functions and risks has changed. In essence, the COVID-19 crisis provides an opportunity for MNEs to revisit their international related party dealings (including supply contracts and transfer pricing models between related parties), just as independent companies are doing, to help their businesses survive the aftermath of the pandemic.

In the event that any changes are made to transfer pricing policies, businesses should be prepared to address any transfer pricing-related questions raised by the tax authorities now or in future years. A change in a transfer pricing policy which is not based on a change in the FAR profiles of the related parties to the dealing, may invite tax authority challenge or scrutiny. Therefore, it will be important that businesses consider and contemporaneously document the changes to positions with regards to their cross-border transactions, using market evidence, so they can support these positions once the COVID-19 crisis abates.

This article was first published in Thomson Reuters’ Weekly Tax Bulletin.